Art and music reflect the essential fact that we humans are not sharing one reality but rather perceiving myriads of different possibilities of reality, all interlaced and happening at the same time. We are all aware that two people might experience the same piece of music or art in entirely different ways. The music or the art work is the same and yet the experience differs.

This hints to one of the most fascinating aspects of music: As an ever-reflecting living prism, music changes and is affected by the setting in which it is presented. As humans we are multi-sensorial creatures: unless we actively shut off our senses, isolating only one at a time, our senses will forever fill out and enrich each other and our experiences. The same piece of music experienced on a train late at night with headphones or in a fully packed concert Hall during a festival are two entirely different experiences no matter if the music is the same. A person in love and a person with a dental appointment will probably colour their experience of the same piece of music quite differently.

A piece of music, however well we might know it, is forever growing, sprouting new limbs, whispering in new voices and our possibility for experiencing it in new ways are endless.

Searching for the familiar un-known

At the Kamfest 2016, the annual chamber music festival in Trondheim, Norway, the Danish composer Bent Sørensen was the year´s composer in residence and brought to the festival his unique flavour of musical landscapes.

From my very first encounter with his music while doing a master thesis Sørensen's works always held a strange and unique fascination. Perhaps it had to do with my lifelong love for jigsaw puzzles which held an endless fascination for a mind who was constantly looking for patterns.

From my very first encounter with his music while doing a master thesis Sørensen's works always held a strange and unique fascination. Perhaps it had to do with my lifelong love for jigsaw puzzles which held an endless fascination for a mind who was constantly looking for patterns.

When listening to music our mind is essentially searching for “form” which means we are forever searching for an underlying pattern, something which will make what we hear "logical" and "understandable" according to our mind. This is however not necessarily a logic and understanding based so much on intellectual concepts as it is based on a sense of relationships, - an acute sense that some parts are closer connected than others and that the entire piece therefore consists of a sort of pattern which is graspable if we are able to conceive it.

The Norwegian composer Arne Nordheim made a rather famous and much quoted comment of Sørensen’s music: "it reminds me of something I have never heard before", pinpointing this strange feeling of familiarity coupled with the sense of encountering something unknown which the music of Sørensen triggers.

The Jigsaw puzzle that never stops

In 2007, Sørensen was composer in residence at Festspillene in Bergen and in one of the concerts, which was given the title "Songs in rings of bells," ten of the composer’s compositions were fused into each other in a long cycle. Some of the works were solo pieces, others were written for chamber ensemble.

According to Sørensen the challenge in organizing the concert laid in discovering the coherence and connection between pieces which were composed at different times, but which still held the same subconscious element of connection, something, he stated, which had always been there.

In a way a composer´s entire output of works might be likened to the pieces of a gigantic jigsaw puzzle where each individual work relates to one piece of the puzzle, excavated with enduring and painstaking integrity from the composer´s unique musical landscape. In the concert in Bergen the fusing of the different pieces woke to life this sense of unfolding of a landscape which continued outside of its visible frames.

Sørensen´s music is all texture and movement, fragments and whispers which give rise to slips of memory. The use of tempos plays with our perception:

Listen to the piece The Deserted Churchyards where, in the beginning, two lines of musical texture move together, one from above and one from below, crossing and departing. In the upper register the fast-moving myriad of notes from the piano and percussion tricks the mind into a perception of a larger, slower moving field of sound that is slowlymeansering downwards, like millions of small rivulets of current creating the larger swellings of a river.

At the end the glockenspiel also triggers the pictures of church bells swallowed slowly by an ever-encroaching sea line (around 7.25).

The multiple realities of art and of humans

Just as all our senses are engaged together to a certain degree in every art-experience we encounter, listening and perceiving art is also a highly co-creative experience.

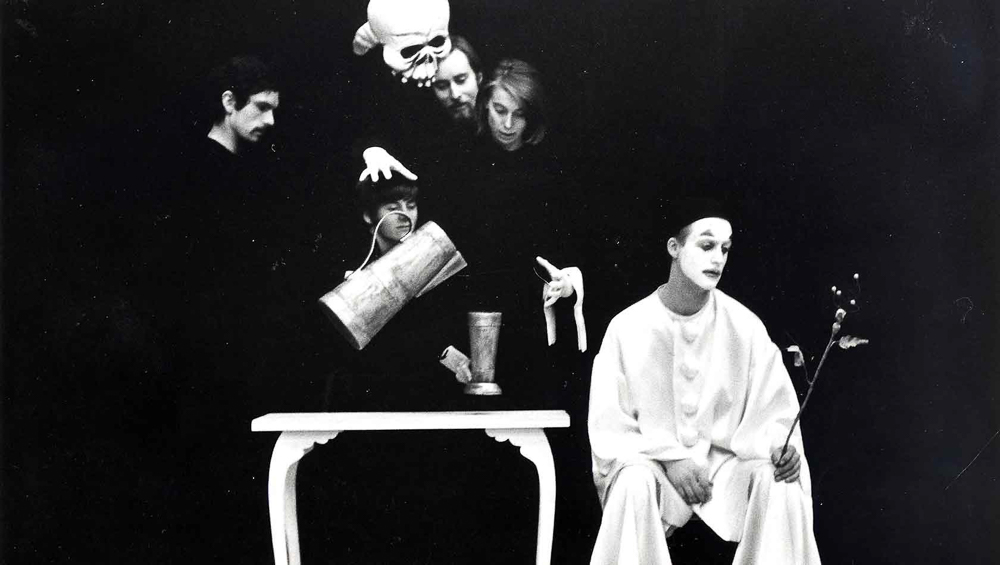

From a staging of the piece “Moon over the Minstrel wagon”. One of the first stagings that used black light theatre in Norway. The piece was a cooperation between my father Karel Hlavaty and my mother Nina Martins

From a staging of the piece “Moon over the Minstrel wagon”. One of the first stagings that used black light theatre in Norway. The piece was a cooperation between my father Karel Hlavaty and my mother Nina Martins

My father worked, among other things, as a director and scenographer at the theatre, providing the visual parts and settings of the performance. His main creed was always that the less visual cues you give the audience, the greater liberty you are granting to their imagination and co-creation of the experience. Theatre, as well as music is a co-op: it demands the active co-operation of everyone involved and that includes the audience/listeners.

Filling in the picture (or the notes)

In the suites for solo cello by Johan Sebastian Bach the cellist has four strings, four fingers and a bow at his or her disposal. Only two strings can be played simultaneously and therefore the possibilities for creating harmony and chords (three or more notes played simultaneously) is limited. How then is it possible to create the impression of more than one voice moving along?

The solution is to involve the listener as a co-creator: in his music Bach often implicates harmony by having the cellist move between fragments of two or more voices. In the listener's mind the fragments merge into two or three separate voices being played simultaneously and thus harmony is created. One way this is done is through arpeggios or broken chords, where the notes of the chord are played after one another but where the listener combines them in his head. Here is an example from the Allemande of the second Suite in d-minor.

Seen in a time perspective the notes are played one after one the other in succession along a horizontal timeline, the hallmark of melody, but in the mind of the listener harmony (the stacking of notes vertically) is nevertheless created.

The only reason why it is possible for a scenographer to depend on the co-creation of the audience or for a composer to depend on the aural jigsaw puzzle-skills of his audience is the knowledge that this is a central part of the human mind: the ability and fascination for filling out the picture, for joining the dots.

Most of us are highly unaware of all the amazing processes happening inside ourselves when we are conceiving art; of how many amazing sensorial connections that are being made and contributing to our overall experience. If we were aware of this, we might perhaps place less of an emphasis on the opinion of others to tell us how to think and feel about what we have just experienced and simply be present in the unique jigsaw puzzle-games of our amazing minds.

Maybe we should all be more in awe over our own creative ability when encountering music or art, an ability without which would render music and art as barren constructions and not as the amazing playgrounds for the mind that they are.

Read more about Miriam Hlavaty at her webpage